Dr. Melissa Lem: Family Physician

“Research shows that mood improves, stress decreases and concentration is enhanced by exposure to trees and green space.” Dr. Melissa Lem, a family physician, describes the growing body of research into the human health benefits of “green time,” barriers to children spending time in nature, and government policies that could increase people’s access to green space in our urban environments.

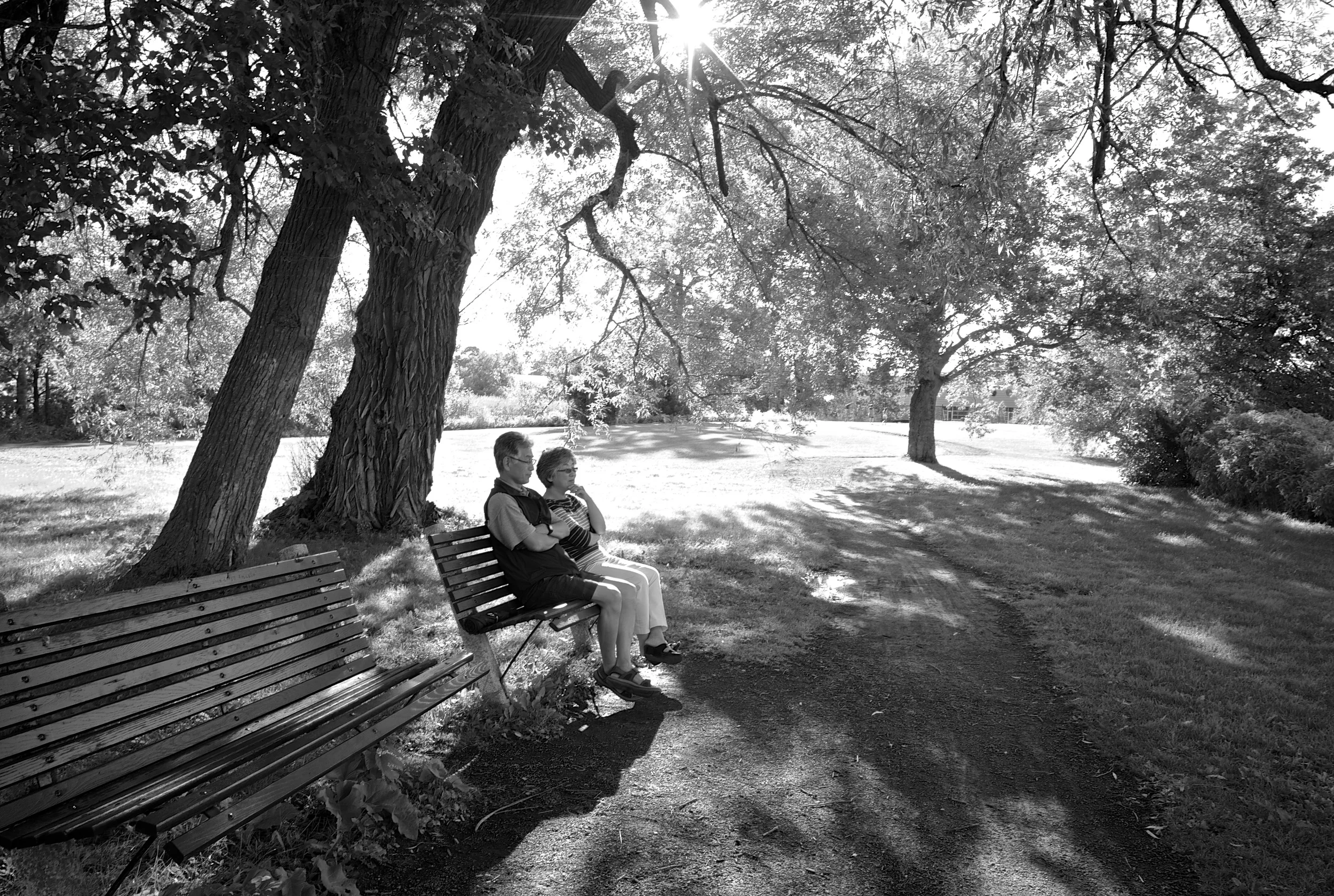

Photos: Jana Dybinski, Faris Ahmed and Chris Osler

Photo: Chris Osler

Q.1. Do you have a favourite childhood memory related to trees?

My favourite childhood memory of trees comes from the first summer I spent camping with my family in Bruce Peninsula National Park. I grew up in the suburbs of Toronto, and it was my first real nature experience. We sat around the campfire during our first night at Cypress Lake, and all I could hear were crackling logs and the wind rustling through the forest. I remember looking up past the swaying silhouettes of mysterious trees against a sky full of starlight, feeling completely at peace and thinking I would be happy spending every night for the rest of my life right there.

Q.2. From your perspective, what is the most important contribution made by trees that makes them so valuable?

Trees—and by extension the islands of nature surrounding them—are incredibly valuable for improving our cognitive and mental health. Whether you’re backcountry hiking or even just looking out an office window, research shows that mood improves, stress decreases and concentration is enhanced by exposure to trees and green space.

Q.3. What effect does spending time in nature have on you personally?

There is nowhere I feel more relaxed or at home than in nature. Even though I’ve lived in cities for most of my life, I can feel my stress levels increasing if I spend too many hours or days without my green fix. I’ve worked in rural and northern communities across Canada from Inuvik, Northwest Territories, to Sioux Lookout, Ontario, and I always make it a priority to locate and get out into local green space to exercise and de-stress after long work days or nights.

Q.4. Why is it important for children to spend time immersed in nature?

Nature is the ultimate jungle gym, both physical and mental, for children at all stages of their lives. For example, children who play in natural settings develop motor skills, balance and coordination faster than those who play in traditional playgrounds. Kids who live closer to green space have lower rates of anxiety and depression. Overweight and obesity are also less common in children who spend more time outdoors.

Photo: Jana Dybinski

Q.5. In your opinion, is there such a thing as “nature deficit disorder”? If so, what is it and how common is it amongst children in Canada?

Nature Deficit Disorder is a clever term coined by Richard Louv in his important book Last Child in the Woods that refers to a constellation of negative health effects caused by a lack of nature exposure, including ADHD, depression and obesity. I do believe that this is a useful term to describe what happens when we deny our natural affinity towards nature. While there are no statistics on the prevalence of NDD because it isn’t an official medical diagnosis, we do see rising rates of screen time among children, which has been linked to inactivity, sleep disorders and poor social skills. More outdoor green time is an antidote to this.

Q.6. Is there an increase in the amount of research carried out recently on the physical and psychological health benefits of spending time in nature? Are more and more physicians taking note of this research and “prescribing” time spent in nature?

There is a growing body of research on the health benefits of nature exposure. As a physician, I’m most excited by studies that show measurable, objective improvements in biomarkers of health and brain function. A 2011 study from Japan demonstrated lower cortisol, or stress hormone, levels among young men who sat in a forest compared to an urban setting for 15 minutes. And one fascinating 2009 Chicago study showed that a 20-minute walk in a park rivalled the concentration-enhancing effects of prescription stimulant medication for children with ADHD! I believe that nature prescriptions are still uncommon in North America, though the Japanese government recognizes shinrin-yoku (literally translated as “forest bathing”) as an official form of health-promoting therapy.

Photo: Faris Ahmed

Q.7. Most Canadians live in urban or semi-urban areas where access to nature is mainly through green spaces such as parks or schoolyards. Is the time spent in urban natural settings as beneficial as experiences in remote wilderness?

There is some evidence to suggest that locations with higher biodiversity are more beneficial for mental health. Parents of primary-school children with ADHD in a 2001 study rated their symptoms as less severe with increasing green-ness of their play settings. A 2010 study of 101 Michigan high schools described higher grades and graduation rates in students who had more access to views of trees and shrubs from their classroom and cafeteria windows, while a view of a lawn had no positive effects. That said, any amount of nature you can fit into your life, whether it be an active commute along a local trail or a coffee break in a local park, is still beneficial.

Q.8. What are some of the barriers children face in spending time in nature?

Parental concern about stranger danger, especially in urban areas, can make it difficult for children to get adequate unstructured green time. Modern children also tend to be overscheduled, and what free time they do have is often spent on television, social media and video games. It’s also important for parents to be better role models for their children and embrace green activities themselves.

Photo: Jana Dybinski

Q.9. In your opinion, what are some of the government policies that would encourage more children to spend time in nature?

The approach should be two-fold: enhancing direct access to nature, and providing incentives for children to spend more time in nature. Bylaws ensuring that new residential developments, especially in urban areas, have protected green spaces and green corridors for the school commute would be useful. Schoolyards should be designed to enhance nature contact; for example, natural playscapes should be favoured over conventional playgrounds, and trees and vegetation should be planted in sight of classroom windows. Tax credits for park passes and nature society memberships would also encourage families to get outside. The federal government will be launching a “Carrot Rewards” app in the fall of 2015 that gives Canadians points for participating in health-promoting activities. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if green time were one way to earn points?

Q.10. Finally, do you have a favourite tree species? If so, what is it and why?

My favourite tree species is the trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides), for its graceful beauty and shimmering sound. My first job was as a rural family physician in Hazelton, northwest British Columbia, where the forests and river valleys were filled with them. When autumn arrived they would paint that beautiful landscape a vivid gold. My house there was also surrounded by trembling aspens, and after long nights of being on call I would walk home, gaze up at and listen to the trees in the morning light, and look forward to hiking among them after catching up on my sleep.